A sharp hiss and a burst of compressed air mold the smooth leather, shaping it into a classic all-American cowboy boot—manufactured not in the U.S., but in a factory on China’s eastern coast.

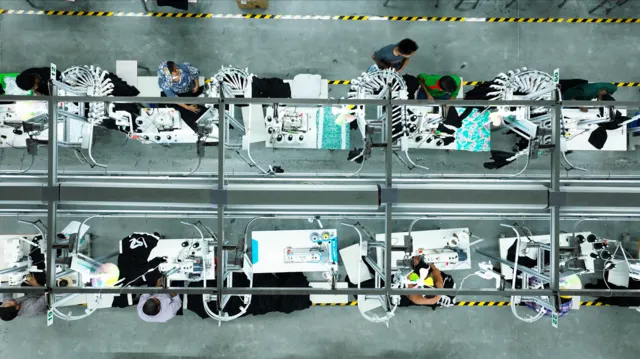

As the assembly line moves forward, the rhythmic sounds of sewing, stitching, cutting, and soldering fill the vast space, echoing against the high ceilings.

“We used to sell around a million pairs of boots a year,” says Mr. Peng, a 45-year-old sales manager who prefers to withhold his first name.

That was before Donald Trump.

The former president’s first term ushered in a wave of tariffs, sparking a trade war between the world’s two largest economies. Now, six years later, with Trump back in the White House, Chinese businesses are bracing for what could be an even more turbulent sequel.

“What direction should we take in the future?” Mr. Peng wonders aloud, his uncertainty mirroring that of countless others whose livelihoods hinge on the shifting tides of global trade.

A Looming Trade Battle

As Western markets grow increasingly wary of Beijing’s global ambitions, trade has become a powerful bargaining tool. This is especially true as China, grappling with economic sluggishness, leans more heavily on exports.

Donald Trump returned to office on a campaign promise to impose sweeping tariffs on Chinese goods. Among his most immediate threats is a 10% levy, set to take effect on February 1.

In addition, he has ordered a comprehensive review of U.S.-China trade relations—giving Beijing a brief window to maneuver while providing Washington with greater negotiating leverage. For now, however, Trump’s harsher rhetoric and tariff measures appear more squarely aimed at U.S. allies such as Canada and Mexico.

Although a direct confrontation with China seems momentarily paused, few doubt that it is on the horizon. The precise number of companies relocating out of China remains unclear, but major brands like Nike, Adidas, and Puma have already shifted production to Vietnam. Meanwhile, Chinese firms, too, are diversifying their supply chains, though Beijing remains a dominant force in global manufacturing.

Mr. Peng, a sales manager at a factory producing American-style cowboy boots, notes that his employer has considered moving operations to Southeast Asia—just as many of their competitors have.

While such a move could secure the company’s future, it would come at a cost: the loss of a loyal workforce. Most employees hail from Nantong, a nearby city, and have spent over two decades working at the factory.

For Mr. Peng, the factory is more than just a workplace—it is home. After losing his wife when their son was young, the close-knit team became his family.

“Our boss is determined not to abandon these employees,” he says, underscoring a difficult choice faced by many Chinese manufacturers navigating an uncertain global trade landscape.

Struggling to Stay Afloat

Mr. Peng understands the geopolitical forces at play, but for him and his colleagues, the focus remains on one simple reality: making a living. The scars of 2019 are still fresh, when the fourth round of Trump’s tariffs—15% on Chinese-made consumer goods, including clothing and footwear—delivered a heavy blow.

Since then, orders have dwindled, and the factory’s workforce has shrunk from more than 500 employees to just over 200. The impact is visible in the empty workstations as Mr. Peng leads the way through the factory floor.

Surrounded by the rhythmic hum of machinery, workers carefully cut leather into precise shapes before handing it off to machinists. Precision is critical—any mistake could ruin the expensive leather, much of which is sourced from the United States.

In an effort to remain competitive, the factory is focused on keeping costs low. Yet, many American buyers are already weighing alternatives outside China, wary of ongoing trade tensions and looming tariffs.

Relocating production, however, would come at a cost: the loss of skilled labor. Crafting a single pair of boots is a meticulous process that takes up to a week—from flattening and shaping the leather to polishing and packing the finished product for export.

This labor-intensive yet highly scalable model has long been the backbone of China’s manufacturing dominance, supported by an unparalleled supply chain developed over decades.

“There was a time when we were constantly inspecting goods and shipping them out—it gave me a sense of fulfillment,” recalls Mr. Peng, who has worked at the factory since 2015. “But now, with orders declining, I feel lost and anxious.”

Once crafted for the rugged terrain of the American West, these cowboy boots have been produced here for over a decade. And this factory’s story is just one of many in Jiangsu province—a key manufacturing hub along the Yangtze River, where industries churn out everything from textiles to electric vehicles.

The Shifting Landscape of U.S.-China Trade

For decades, China has shipped hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of goods to the United States annually, solidifying Washington as its largest trading partner. This relationship flourished until Donald Trump’s presidency, during which tariffs and trade tensions disrupted the status quo. However, even under his successor, Joe Biden, most of these tariffs remained intact as U.S.-China relations continued to deteriorate.

Beyond the United States, the European Union has also imposed tariffs—specifically targeting Chinese electric vehicle imports—accusing Beijing of overproduction fueled by state subsidies. Trump has echoed these concerns, arguing that China’s “unfair” trade practices undermine foreign competitors.

From Beijing’s perspective, such accusations reflect broader Western efforts to stifle its economic growth. Chinese officials have repeatedly warned Washington that a trade war will yield no winners, while simultaneously expressing willingness to engage in dialogue and “properly handle differences.”

For President Trump, who has described tariffs as his “one big power” over China, negotiations appear inevitable. However, the terms he may demand in return remain uncertain.

During his first term, Trump initially sought closer ties with Beijing, even traveling to China to request President Xi Jinping’s assistance in facilitating a meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. This time, some speculate he may seek Xi’s influence in brokering a deal with Russian President Vladimir Putin to end the war in Ukraine—an issue on which he recently remarked that China holds “a great deal of power.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s proposed 10% tariff hike is reportedly driven by concerns that China is supplying fentanyl to Mexico and Canada, potentially positioning this issue as a key bargaining chip.

Additionally, given Trump’s previous encouragement of a bidding war over TikTok, he may also use trade negotiations to influence the app’s ownership—or secure access to its highly valuable technology, which Beijing has the authority to approve or block in any potential sale.

Whatever the terms of a potential agreement, it could serve as a reset for U.S.-China relations. However, the absence of a deal risks cutting short any possibility of a diplomatic “second honeymoon,” potentially setting the stage for a more confrontational dynamic between Trump and Xi.

Uncertainty is already weighing on businesses. According to an annual survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, just over half of its members express concerns about further deterioration in U.S.-China relations.

While Trump’s recent rhetoric on China appears somewhat softer, the underlying strategy remains unchanged—leveraging the threat of tariffs to push buyers away from China and encourage a resurgence of American manufacturing.

Yet, while some Chinese businesses are indeed relocating, they are not heading to the United States.

Shifting Supply Chains

About an hour outside Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, entrepreneur Huang Zhaodong has established a new factory to accommodate growing demand from major U.S. retailers, including Walmart and Costco.

This marks his second factory in Cambodia, and together, they produce half a million garments per month, ranging from shirts to underwear. Inside the facility, an automated production line moves hangers carrying cotton trousers from station to station, where workers insert elastic waistbands and finish hemlines with precision.

When prospective U.S. customers ask the inevitable first question—where is he based?—Mr. Huang now has the ideal response: not in China.

“For some Chinese firms, their clients have made it clear: ‘If you don’t move production overseas, we’ll cancel your orders,’” he explains.

The ongoing tariff battle presents difficult choices for both suppliers and retailers, and the financial burden is not always straightforward. Sometimes, the cost is passed on to the consumer.

“Take Walmart, for example. I sell them garments at $5 per unit, and they typically mark up prices by a factor of 3.5. If tariffs push my price to $6, their retail price will increase accordingly,” says Mr. Huang.

But more often than not, the supplier absorbs the impact. If his production remained in China, an additional 10% tariff would cost him approximately $800,000 (£644,000) annually—more than his entire profit margin.

“It’s an unsustainable model. Under such tariff conditions, manufacturing clothing in China simply isn’t viable,” he admits.

The Broader Implications

Current U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports range from 100% on electric vehicles to 25% on steel and aluminum. Until now, key consumer electronics—such as televisions and iPhones—have been largely exempt.

However, Trump’s proposed 10% blanket tariff could significantly alter the landscape, affecting virtually every Chinese-made product entering the U.S. market—from toys and teacups to laptops and home appliances.

Shifting Supply Chains and Expanding Influence

Mr. Huang believes the shifting tariff landscape will prompt even more factories to relocate. Around him, new workshops continue to emerge, as Chinese companies from textile hubs such as Shandong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Guangdong set up production for winter jackets and woolen garments.

According to a report by insight and analysis firm Research and Markets, approximately 90% of Cambodia’s clothing factories are now Chinese-run or Chinese-owned. China also accounts for half of Cambodia’s foreign investment, with Chinese-funded loans financing 70% of the country’s roads and bridges, as reported by Chinese state media.

The presence of Chinese businesses is evident in daily life: restaurant and shop signs are often displayed in both Chinese and Khmer, Cambodia’s local language. Even a key ring road in the country’s capital is named Xi Jinping Boulevard in honor of China’s president.

A Strategic Global Expansion

Cambodia is just one of many nations benefiting from China’s extensive investments. Under President Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has poured resources into infrastructure and trade projects worldwide—efforts that simultaneously bolster its geopolitical influence.

China’s economic ties are now deeply embedded across multiple regions. Chinese state media reports that over half of China’s total imports and exports now come from Belt and Road partner countries, with a significant portion concentrated in Southeast Asia.

This diversification provides China with flexibility in global trade—allowing it to navigate economic pressures while strengthening its foothold in key markets.

According to Kenny Yao from AlixPartners, a consultancy firm advising Chinese businesses on navigating tariffs, the current shift in global trade strategies has been years in the making.

“During Trump’s first term, many Chinese firms underestimated his tariff threats,” Yao told the BBC. “Now, they are asking whether he might extend tariffs beyond China and target supply chains in other countries.”

To mitigate future risks, Yao advises Chinese businesses to diversify their operations, exploring new markets such as Africa and Latin America—a move he acknowledges as challenging but strategically beneficial.

China’s Strategic Positioning

As the United States prioritizes domestic interests, Beijing is positioning itself as a stable business partner—and some indicators suggest this strategy is working.

A survey by the Iseas Yusof-Ishak Institute in Singapore reveals that China has overtaken the U.S. as the preferred economic partner for Southeast Asian nations.

Despite production shifting abroad, China’s supply chain remains dominant. Sixty percent of the raw materials used in Mr. Huang’s Phnom Penh factories still originate from China, ensuring that a significant share of profits continues to flow back home.

Meanwhile, China’s export sector remains robust, driven by increased investment in high-end manufacturing—including solar panels and artificial intelligence. In 2023, China recorded a historic trade surplus of $992 billion, following a 6% year-on-year increase in exports.

Uncertainty Ahead

However, businesses in Jiangsu and Phnom Penh remain cautious, bracing for a potentially turbulent period.

Mr. Peng hopes for constructive discussions between Washington and Beijing, advocating for tariff policies that remain “reasonable” and avoid an all-out trade war.

“Americans still need these products,” he remarked before setting off to meet new clients, underscoring the enduring demand for Chinese-manufactured goods—wherever they may be produced.